A delightful story this month: Satish Kumar, the Editor Emeritus of Resurgence & Ecologist magazine, used his invitation to speak at the renowned London School of Economics to challenge them to reconstitute as the London School of Economics and Ecology!

In Kumar’s telling, he enquired, over tea and cake, about LSE’s ecological offerings, to which he was informed there were several courses which integrated environmental issues into economic frameworks.

‘But environment and ecology are not the same,’ he replied. ‘Ecology means understanding of the entire ecosystem and how the diverse forms of life relate to each other.’ To which the response was: ‘That is too broad a concept. Our courses are much more specialized.’

I like the story for two reasons. First, I enjoy the thought of a distinguished guest speaker politely asking his hosts over refreshments whether they have considered being the opposite of what they are! It strikes me that more guest speakers at more events might usefully ask the question.

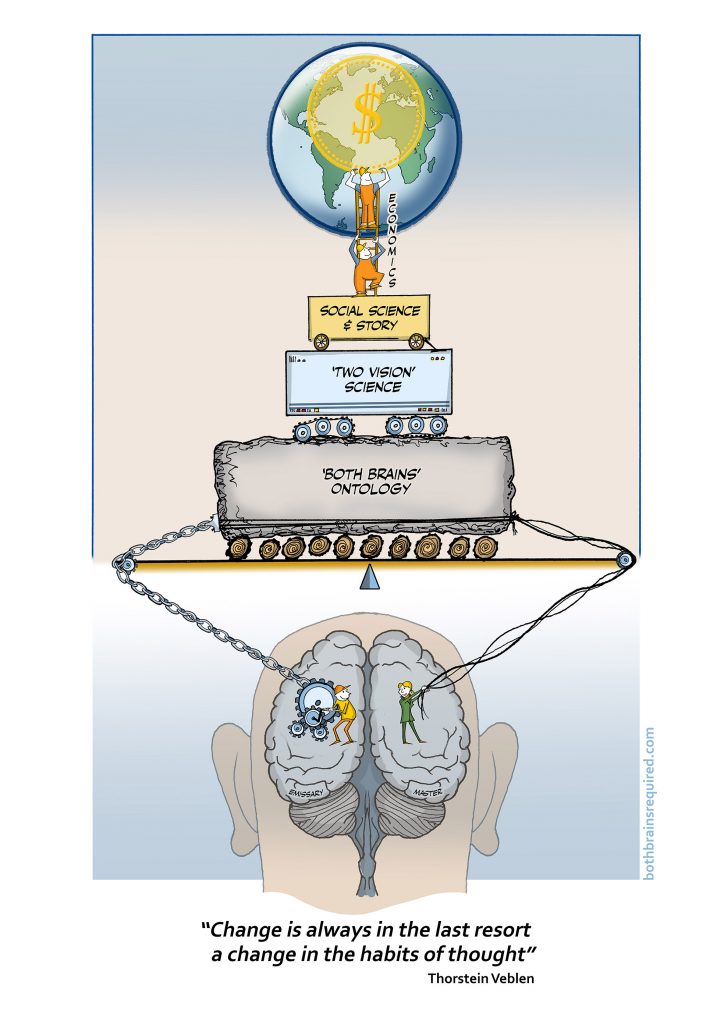

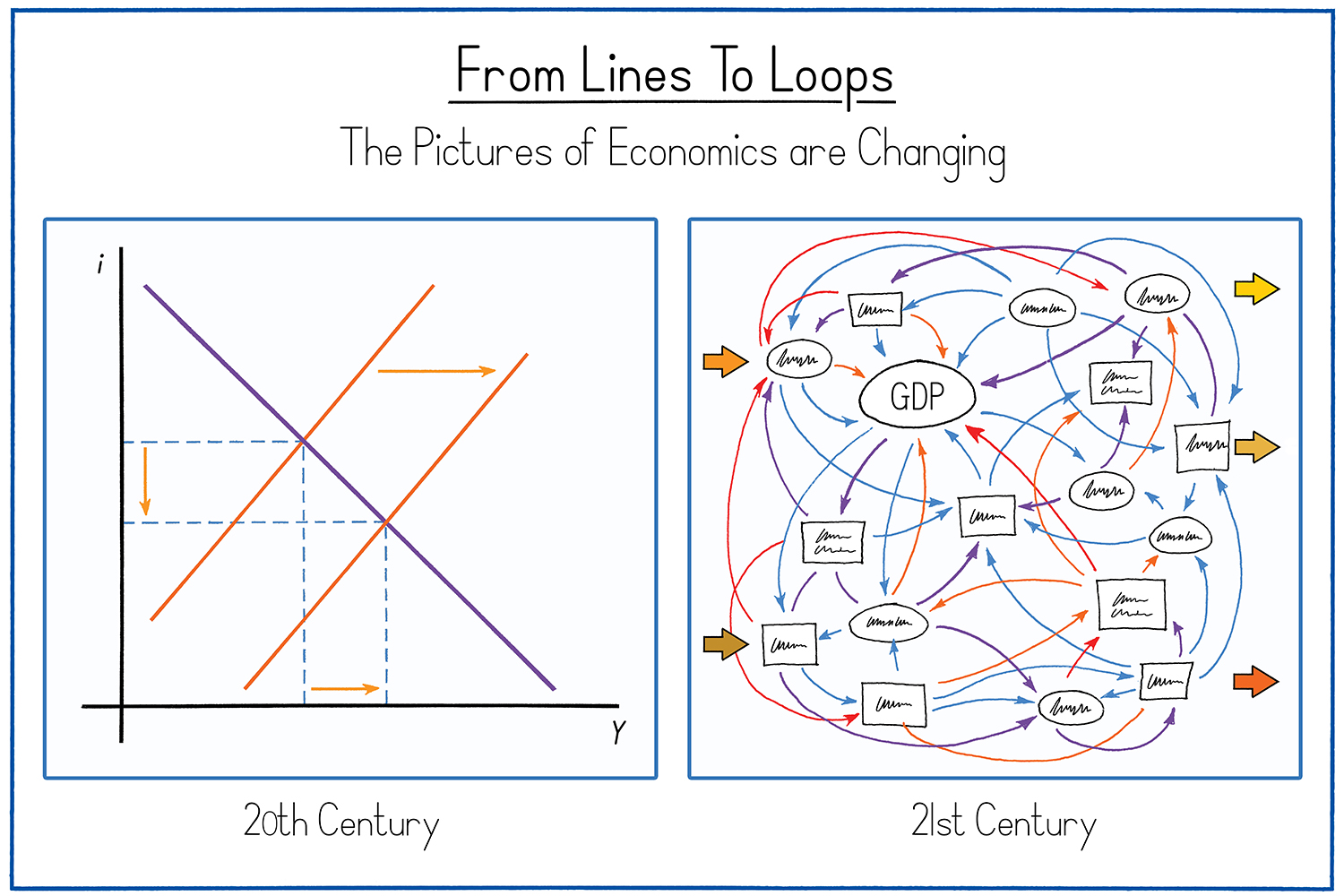

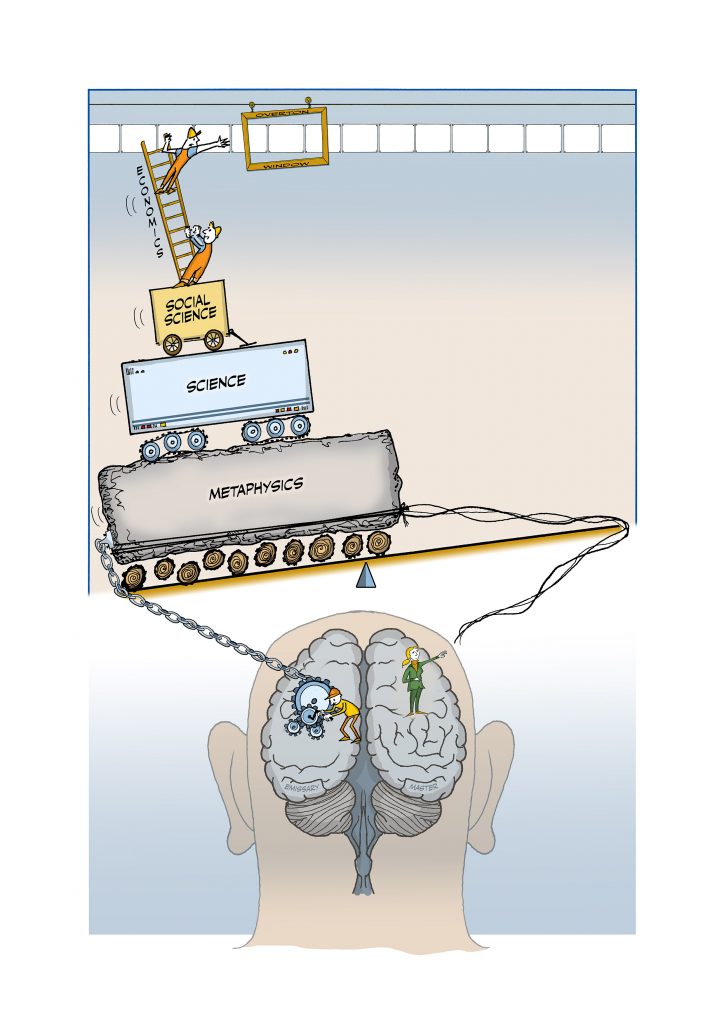

The more serious reason is that Kumar’s provocative idea, and the defensive response, catches the very essence of our ecological sustainability challenge: that economic thinking still fails to grasp the sort of thinking ecology is, particularly ecology’s focus on relation.

I believe this remains poorly understood because I, too, missed it for a long time. Twenty-five years ago, I attained one of the first ‘environmental economics’ degrees (at another London university then unique in offering such a course). With best of intentions, we all – professors and students alike – believed that environmental economics was a proper union of economic and ecological thinking, but it is now clear to me that it was no such thing. Instead, it was the appropriation of some ecological concerns into a way of thinking that remained steadfastly economic.

The real significance of this is less about improving university programs and more because it is exactly this misunderstanding that underlies our continued failure to solve major ecological problems despite considerable attention now paid to them.

Today, we live in a market-centric society, profoundly informed by – and so daily reinforcing – an economic mindset. Economic thinking is what powers the business and investment worlds. We have become ‘consumers’ and ‘human capital’.

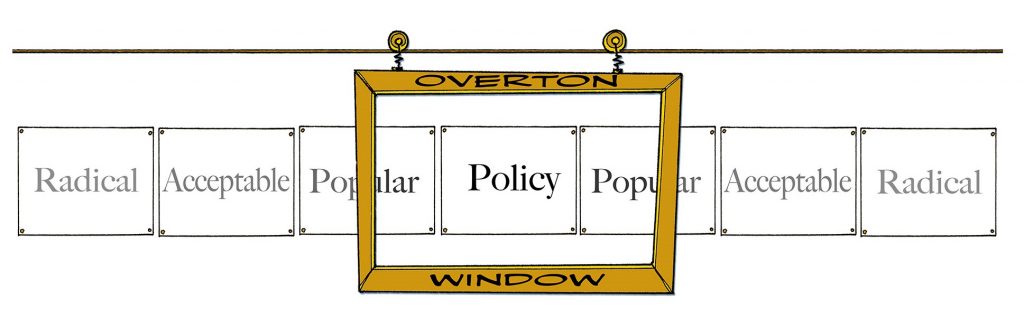

Consistently, we are trying to solve our sustainability problems in market-friendly or market-tolerable ways, spearheaded by an ESG (environmental, social and governance) movement within the private sector and by related ambitions for ‘green growth’ and ‘more sustainable capitalism’. Alas, these ideas are simply real-world manifestations of ‘environmental economics’ thinking. They represent a comprehension of the problems to which ecology points, but a failure to grasp the form of remedy to which an ecological perspective leads.

…

Full 35 page paper here (PDF): Can Economics Grasp What Ecology Says?

The conclusion (!):

As published by Responsible Investor, February 2021:

RI long read: Can ESG grasp what ecology says? (responsible-investor.com)

Recent Comments